Wrestling, Symbolism, and the Paradox of the Snake

Some thoughts on my favorite sculpture, its association to myth, and its reflection in behavior

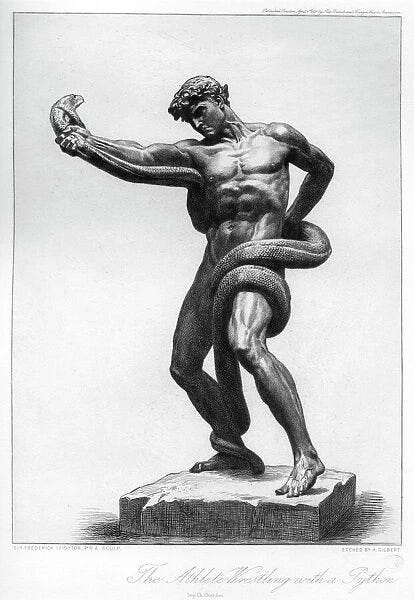

The sculpture depicted above, entitled An Athlete Wrestling with a Python, has recently captured my attention. Created by Fredric Leighton in the late 1800s, the piece is said to be based on the myth of Apollo and his struggle with the python of Delphi. The symbolism of the snake, in contexts as seemingly varied as ancient Egyptian myth and the biblical stories, is paradoxical: representing healing in some contexts and death in others. The man symbolizes the masculine ideal, evident through his characteristically Grecian physique and the mastery he displays over predation. Although not a traditional depiction of wrestling, the man has grappled with the snake and found a dominant position. Having established the characters as symbolic, the action so masterfully evoked connects to other sources that have influenced Western culture.

Marcus Aurelius, the Roman emperor and stoic, wrote in Meditations that life was more like wrestling than dancing. His logic implies that life is more usefully understood as a competitor, as an opponent, than a collaborative partner. Echoing eastern wisdom in implicit message – that life is suffering – but unique in behavioral prescription, Aurelius’ argument points readers toward framing trials as opportunities to bolster strength and resilience.

The biblical story of Jacob recapitulates this idea. Alone after sending his family ahead because of an impending attack by his brother Esau, Jacob wrestles with “a man until the breaking of day.” Scholarly interpretation of this passage presents the man as God. Jacob emerges from the encounter with an injured hip and a new name, Israel, which in Hebrew means “to struggle with God.” Jacob receives this name after asking to be blessed by God, something he has been seeking most of his life but has not earned. After the wrestling match lasting all night, during which he was close to losing everything, Jacob receives a blessing that is proportional to the difficulty of his trial.

Jacob could have received this blessing in a variety of ways, though, besides a wrestling match. He might have repented for the lies he told in his past or expressed remorse to his brother Esau; but God gave him a physical test in which Jacob was forced to utilize his power. It is almost as if God wanted to see how much fight Jacob had in his spirit, to give Jacob the opportunity to prove that his numerous failures and difficulties had not conquered him. This story also presents a curious facet of God, if one makes the association between God and the sum of all goodness: that at times goodness is an award received at the culmination of a long struggle.

The act of wrestling connects the sculpture to its mythic origins and the biblical story of Jacob. It presents the human struggle as a contest; as a pitting of humans against various forces that oppose and instruct us. The opponent changes, but the behavior remains.

I started training Brazilian Jiu Jitsu in the summer and, although not specifically wrestling, the art offers practitioners important feedback about their strength and ability to persevere. This discipline extrapolates on the fundamentals of wrestling and offers more opportunities for submission of an opponent. Jiu Jitsu translates from Japanese as “the gentle art”; the use of “gentle” is certainly paradoxical but refers to the focus on submissions that do not harm the opponent, but force them to forfeit the contest because of the threat of harm. After five months of training, I competed yesterday for the first time in a tournament held by the gym I attend. This experience was instructive and provided me insight into grappling as both a symbolic and physical act.

In the Pulitzer Prize winning book The Denial of Death, Ernest Becker writes that “the essence of man is really his paradoxical nature, the fact that he is half animal and half symbolic.” Wrestling is one opportunity to see this truism encapsulated in a behavior: the individual grapples physically with an opponent and symbolically with life’s struggles, with the self, with finding meaning. What I have found, though, is that understanding the symbolism of wrestling is often not sufficient to influence one’s perception: stepping into the arena is required. To learn the techniques of jiu jitsu is to put them in practice against an opponent, to engage. This is the bridge between our symbolic nature and our animal nature. Strength is not known but through a test.

The adolescents I work with must enter into the process of behavioral learning to overcome their illness – Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Obsessions are thoughts or images that are distressing and constant; compulsions are behaviors one engages in to assuage the anxiety. The gold standard of treating this illness is exposure therapy, in essence exposing the individual to the object, situation, or person that causes obsessional thinking in order to learn that they can withstand uncomfortable feelings without engaging in compulsions. Fear is often debilitating for these young people, but they learn to have a healthier relationship with fear through voluntary interaction with it, through wrestling with it. Through this action, the paradox of the snake finds meaning: the thing that destroys can also heal, if contended with. The snake in Leighton’s sculpture is fear itself, intent on suffocating its opponent. The man is all of us. Victory is uncertain; injury, to the hip or otherwise, is possible. The necessity of engagement still remains.